#CHILI : "Defending #Allende" by Ariel Dorfman (#NYRB)

_

On September 4, 1973, an enormous multitude of Chileans—I was one of them—poured into the streets of Santiago to back the besieged government of Salvador Allende. Ever since he had won the presidency three years earlier with 36.6 percent of the vote in a three-way race, forces from inside and outside the country had been conspiring to destroy his attempt—the first in world history—to build a socialist state through nonviolent, democratic means. One shout from a chorus of voices echoed through the air: “Allende, Allende, el pueblo te defiende,” emphasizing the need to defend the president. After one thousand days of unrelenting opposition, his enemies seemed close to orchestrating a coup d’état that would wipe “the Marxist cancer” from Chilean society forever.

Allende felt cornered. I knew this because, though only thirty-one at the time, I had been working for the previous two months at the presidential palace of La Moneda as a cultural and press adviser to Fernando Flores, Allende’s chief of staff, and our reports indicated that many admirals and generals were openly plotting against him. Allende nevertheless remained hopeful. Unlike that of so many Latin American nations, Chile’s military had a lengthy tradition of respect for constitutional rule, with smooth transitions between presidencies guaranteed by its strict nonintervention in political affairs. Thus far the army, at least, had continued to profess loyalty to the government. I remember Flores telling me with glee that General Augusto Pinochet, the head of the army, was in his pocket, nicely tied up: “Este Pinoccho! Lo tengo en este bolsillo, bien amarrado.” Allende also believed this was the case, but he placed his real faith in the mobilization of el pueblo (a term that encompasses several meanings in Spanish: the people, the masses, the poor, the great unwashed). And the Chilean pueblo had many reasons to support the Allende experiment.

His cabinet—the first to include a peasant and an industrial worker as ministers—had undertaken a series of reforms, the most impressive of which was the nationalization of the enormous copper mines, until then owned by predatory US corporations. It had also nationalized the mining of minerals like nitrate and iron, as well as many banks and large factories, a number of which were being administered by those who worked in them.

An ambitious agrarian reform had been handing over latifundios—large rural estates—to the peasants who had toiled on them from time immemorial; by 1973 almost 60 percent of Chile’s arable land had been expropriated.

Though some of these initiatives (and blunders by the relatively dysfunctional government of the Unidad Popular, the alliance of left-wing parties that had supported Allende for president) caused economic and financial disruptions, there had been a remarkable redistribution of income and services to the most underserved members of society. Other measures revealed Allende’s priorities: a half-liter of milk daily for every child; cabins erected by the ocean so workers could vacation with their families (most had never seen the Pacific before); the acknowledgment of indigenous identities and languages; the publication of millions of inexpensive books that were sold at newspaper kiosks; and major advances in health, affordable public housing, education, and child care.

All this was accompanied by a blossoming of culture, particularly in music, mural painting, and documentary film. But perhaps more important than these material advantages was the dignity felt by so many disadvantaged citizens, their sense that they were now the central characters of their nation’s history.

I had one of the most moving epiphanies of my life on the night of Allende’s election on September 4, 1970. After listening to him promise a delirious crowd that he would be el compañero presidente when he entered La Moneda in two months’ time, I wandered along the streets of Santiago with my wife and friends and witnessed the wonder, pride, and determination on the faces of workers and their families as they walked through the center of the city. Unsurprisingly, then, in April 1971 the Unidad Popular parties received nearly 50 percent of the vote—a plurality—in municipal elections, which was interpreted by The New York Times as “a popular mandate to push ahead with [Allende’s] revolutionary Socialist program.”

Momentum seemed to be with us, but formidable barriers remained. Months before Allende’s victory, on June 27, 1970, Henry Kissinger, President Nixon’s national security adviser, indicated what American policy would be regarding the Chilean road to socialism: “I don’t see why we need to stand by and watch a country go communist due to the irresponsibility of its people. The issues are much too important for the Chilean voters to be left to decide for themselves.” Once Allende won—in spite of an American-funded campaign of misinformation that depicted him, a man of impeccable democratic credentials, as a Communist stooge—the next step was to try to stop his inauguration. A CIA-financed terrorist group killed General René Schneider, the commander in chief of the army, who was committed to the rule of law. When Allende was nonetheless sworn in on November 3, covert operations were launched to “make the economy scream,” per Nixon’s instructions.

Over the following years, an international credit squeeze of both private and public funds strangled Chile. Efforts to renegotiate the foreign debt were hampered, copper exports were stalled in reprisal for nationalization, technological expertise was denied, and essential imports (including parts needed to repair machinery and trucks) were prevented from reaching the country. In December 1972 at the UN General Assembly, Allende declared, “before the conscience of the world,” that his country was being subjected to an invisible blockade from abroad that was meant to create chaos and foment a coup.

Such chaos could not prosper without allies in Chile. The US funneled funds to bolster the right-wing Partido Nacional and to persuade the centrist Christian Democratic Party to oppose Allende. Equally consequential was substantial support for the media hostile to the socialist project, particularly El Mercurio, Chile’s main newspaper. All these actions influenced public opinion as well as Congress, where the Unidad Popular was a minority.

A coup always seemed a possibility.

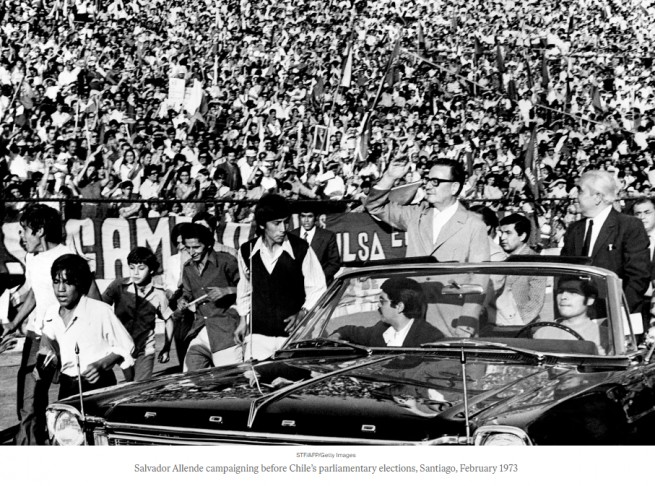

But Allende’s enemies in Chile hoped to oust him through legal means by winning a majority in the March 1973 parliamentary elections, which would allow them to impeach him and remove him from office. The economic situation was dire as those elections approached. Galloping inflation, a thriving black market, and critical shortages of food and staples seemed to be eroding the government’s popularity. The uncertainty was enhanced by insurrectionary strikes by right-wing entrepreneurs, miners, and truck drivers that dealt severe blows to production and distribution. And extensive sabotage and terrorist acts were being carried out by fascist militias flaunting Nazi paraphernalia.

Not all of Allende’s problems came from the foes to his right. Even before his victory in 1970, many left-wing militants had viewed with suspicion his confidence that he could use the bourgeois legal system to achieve radical change. That was only possible, they claimed, if total power was in the hands of the working class and its revolutionary vanguard, which would mean an inevitable confrontation with the military. This thesis was supported by many within Allende’s Socialist Party but mainly by the Movimiento de Izquierda Revolucionaria (MIR, the Revolutionary Left Movement), which, like so many groups of my generation in Latin America, was inspired to embrace armed struggle by the example of Fidel Castro and Cuba.

As soon as Allende was elected, the MIR incessantly pressed the government to go beyond the limits of its own program. Certain that Allende, no matter how “reformist” he might be, would not repress them (they were right), the MIR encouraged workers to occupy factories that were supposed to remain in the private sector and incited peasants in the countryside and the homeless poor in the major cities to seize land that had not been targeted for expropriation. This situation—ominously amplified by the media being subsidized by the CIA—gave the impression that the president had lost control of his own partisans and would, therefore, be unable (or perhaps unwilling) to honor his vow to remain within the legal system. This eroded the trust of those citizens—mostly from the middle classes (small entrepreneurs and shopkeepers, professionals, technicians), but also workers and shantytown dwellers who were anti-Marxist and also patriotic and antioligarchic—whose support was essential, at least in theory, for the Unidad Popular to win a majority in parliament. The insecurity created by the actions of the extreme left, which were tolerated by the government, fed into the wariness that many Chileans already harbored about an administration brimming with Communists who owed allegiance to Moscow and socialists enamored of Che Guevara.

And yet, despite all these difficulties, Allende’s coalition gained seats in Congress in May 1973 with 44.23 percent of the vote, down from nearly 50 percent two years earlier but up eight percentage points from Allende’s showing in the 1970 presidential election. Having failed to achieve a veto-proof majority, the opposition, instead of waiting for the 1976 presidential election to defeat the Unidad Popular, now concentrated on creating the conditions for a military pronunciamiento, as a putsch is often called in Spain and Latin America, where armed forces traditionally speak out before deposing a government, pronouncing words to indicate their motives.

But the people could also speak out. That show of popular support for Allende on the third anniversary of his September 4 victory marked one last occasion for a mobilized populace to send a message of strength and defiance to the armed forces, warning them not to destroy the democracy they had sworn to uphold.

Although during the day I worked at La Moneda, that night I joined a vociferous group of compañeros and militants who marched down the Alameda, the central avenue of the capital, waiting for hours to pass by the presidential palace and catch a glimpse of our leader. As soon as we saw him next to his wife, Tencha, waving a handkerchief from a balcony that overlooked the Plaza de la Constitución, we intensified our chant, our vow that the pueblo would defend Allende.

We kept roaring that oath, even after we turned the corner and left him behind, and then we did something that I still recall, fifty years later, with a tide of nostalgia and emotion. We went around the block and smuggled ourselves into the next colossal contingent of militants so we could pass by the same spot again, as if we wanted to make sure he was still there—though also as if we were saying good-bye to our president. We did not know—or did we have an inkling?—that we were also saying good-bye to ourselves, to who we had been and what we had aspired to, good-bye to a way of life and dreams, good-bye to the country that would soon change.

We may have had an intuition that the battle for memory—a battle that has continued to this day—was already beginning. We were trying to fix that moment so that it would not be forgotten, so that when the story was told that Allende had been alone as the coup materialized and nobody came to the rescue, we could point to that march and to so many actions during those years in defense of what he stood for, use that memory to deny the lies of his enemies and the erosion of time. We would have to defend him when he was gone. Maybe that was what, in retrospect, we were really doing: envisaging a future with and without him.

Maybe we already knew that we were going to lose.

One week later, on September 11, 1973, a military junta, headed by our supposed man-in-the-pocket, Augusto Pinochet, and representing the full fury of the army, navy, air force, and carabineros (national police), made its pronunciamiento, which turned out to be considerably stronger than the words shouted to the wind by our scattered throats: Allende had been deposed and the junta would rule “only for as long as circumstances demand.” When the president refused to resign, the military shelled the palace from the air and the ground. After many hours of combat during which Allende, along with a handful of bodyguards, functionaries, and close friends, engaged in armed resistance, La Moneda lay in smoldering ruins and the president was dead.

It was not until the next day, after Allende’s body had been buried in an unmarked grave in a seaside cemetery in Viña del Mar, that the junta declared he had committed suicide, a claim that was, for many years, repudiated by his family and followers as well as by public opinion worldwide. Gradually the elite of the left in Chile, including Allende’s widow, began to accept that he had taken his own life, though many doubts still remain, and most Chileans of all ideological stripes whom I have consulted over the years insist that he was murdered, something that most people abroad also believe.

Whatever the cause, Allende’s death was the first of many to come. The military had not hesitated to raze the lovely neoclassical building that since 1845 had been the seat of the nation’s government and that had served as Chile’s mint in colonial times (hence its name, La Moneda), and it was certainly not reluctant to punish and persecute Allende’s supporters. Due to a chain of fortunate accidents, I survived the coup, but most of those who served with me as advisers at La Moneda were executed almost immediately, while Allende’s prominent ministers and closest friends were flown to a concentration camp on a freezing, windswept island in Patagonia.

Books were burned publicly, shantytowns raided, students and professors expelled from schools and universities. Detention centers in which prisoners were tortured and executed sprang up all over the country. (In Santiago the National Stadium was converted into one.) Freedom of the press and assembly were abrogated; Congress was dissolved, as were all political parties, trade unions, and nongovernmental organizations. The only institution left in place was the judiciary, which had opposed Allende’s measures and soon showed its subservience to the new masters of Chile: when family members petitioned the courts to learn the whereabouts of their missing relatives, no habeas corpus was issued. Indeed, there were occasions when the judges mocked the wives, suggesting they were so ugly that it was no wonder their husbands had run off.

Disappearance became the regime’s iconic form of repression. It allowed the authorities to eliminate troublemakers without being held accountable, leaving families and friends in the inferno of never knowing if the loved one was dead or still alive and being endlessly tormented. There was no burial site or mourning, only the inchoate fear that this sort of retribution could be doled out to anyone exhibiting the slightest sign of dissidence.

Besides being a way of spreading grief and terror, disappearances laid bare what the dictatorship, counseled by archconservative civilians, intended to inflict on Chile itself: to disappear its past, to systematically demolish all vestiges of the welfare state, an array of civil rights that generations had fought for, and a communal notion of a country that took care of its own. In its place, Chile became a laboratory for Milton Friedman’s neoliberalism. The new regime applied the pain of “shock therapy” to a captive land.

Instead of a shining example of a country that could peacefully aspire to a radically just social order, we were turned into a model of extreme free market economics that was imitated around the world.

Any challenge to the new rulers or their “reconstruction” of Chile to serve the interests of foreign corporations and local monopolies was met with maximum violence. Behind such brutality lurked a fear—perhaps a certainty—that those millions of Allendistas would not be easily deterred, that they would resist, that our president was still alive in the utopia of our hearts, that we would emerge from the shadows.

Those who betrayed and overthrew Allende may have been haunted, as we were, by his last words from La Moneda that day, just before the last loyalist radio was silenced: “El metal tranquilo de mi voz ya no llegará a ustedes” (You will no longer hear the serene metal of my voice). In that speech, Allende excoriates the military and promises that they will receive some form of punishment, even if only a moral one, in the future. He tells his followers not to let themselves be humiliated but also to avoid confronting the soldiers patrolling the city and countryside—advice that saved thousands of lives. But what has resonated most, the words that adorn hundreds of monuments erected in plazas, streets, and playgrounds across the world, is his prophecy that someday the grandes alamedas, the great avenues lined with trees, would open for the free people of tomorrow to walk through.

He was right to give us hope, to offer that prophecy during his final farewell. But once he was dead, it was up to the mourners he left behind to figure out how to survive and resist and forge an alliance that would defeat the dictatorship and perhaps make those luminous words about the grandes alamedas come true.

On September 4, 1990, Allende finally received the triumphant funeral his enemies had denied him. Despite a concerted effort to denigrate him from the day of his death (it was said that he was a corrupt, cowardly drunkard, a sexual deviant who had orgies with nubile girls, a traitor who had secret plans to assassinate the officers of the armed forces and their families and to turn the country into a second Cuba), his mythical stature had only grown over the years, culminating in this public homage. It was orchestrated by the government of the Christian Democrat president Patricio Aylwin, who had taken over from a reluctant and embattled Pinochet when democracy was restored in March 1990. The date of the funeral was carefully chosen to coincide with the twentieth anniversary of Allende’s victory in the 1970 elections.

As I waded through the gigantic, seething, raucous crowd that had gathered in the Plaza de Armas in hopes of catching a glimpse of the dead president’s coffin as it left the cathedral, where a mass was being celebrated in his honor, for a moment I harbored the illusion that time had stood still. The chant of Allende, Allende, el pueblo te defiende transported me back to that march seventeen years earlier in front of La Moneda, and here again was that pueblo, battered and bruised and persecuted; here were these men and women and their progeny who had resisted with enormous sacrifices and courage and cunning the onslaught of the dictatorship and made this day possible by refusing to forget their dead leader.

The illusion could not last. Too much had changed. Those crowds were being tightly controlled, kept away from the official ceremonies—both at the cathedral and at the cemetery where the remains were deposited in a specially designed mausoleum. In the cathedral, standing side by side next to Allende’s family and his most eminent collaborators, were some of his fiercest rivals, most notoriously Aylwin, who as head of the Senate in 1973 had refused Allende’s offer to negotiate a resolution to the constitutional crisis confronting the government and Congress, thereby facilitating the coup.

In his speech that day at the cemetery, Aylwin did not hide his differences with the former president, while emphasizing Allende’s statesmanlike qualities and service to democracy. But we should not dwell on the past that divides us, he said. This occasion was a reencuentro, a reunion and reconciliation between Chileans whose disagreements had brought on the dictatorship.

That reencuentro had not been an easy one. It entailed a painful reflection on our part about the errors: we had promised paradise and ended up in hell. There were two main analyses of what had gone wrong. The MIR argued that the premise that radical change can be undertaken through the ballot box was to blame, and that consequently the only road ahead was an armed struggle for total power, with no hesitation to use violence against merciless and hypocritical enemies who had jettisoned democracy as soon it did not serve their interests.

This suicidal thesis was not what ultimately prevailed among most of Allende’s followers. Profound changes could not be imposed from a minority position; a grand multiclass alliance was required.

Resistance to the dictatorship should be based on appealing to Chileans’ enduring respect for democratic traditions and institutions that had roots in a century of nonviolent civic struggle, an ideal shared by the middle classes and some workers alienated by the pace of Allende’s revolution. Most of them were represented by the reformist Christian Democrats, who had often espoused progressive policies (their program in 1970 had been only marginally different from that of the Unidad Popular) but who felt that the revolutionary government was ruining the country. Led by former president Eduardo Frei, they had paved the way for the coup, trusting that the military would soon call elections that they would handily win.

Some left-wing members of the party had strenuously denounced the junta and soon most others actively rejected its reactionary policies, which opened them up to persecution.

The slow convergence of socialists and Christian Democrats, overcoming many years of bitter conflict, was spectacularly successful: Pinochet was trounced in a 1988 plebiscite on whether he should remain president when civilian rule was restored, and then he was humiliated again when Aylwin won the presidency. There were limits, of course, to what the new coalition could accomplish. This was partly because of how the dictator’s fraudulent 1980 constitution thwarted major changes to neoliberal policies and prevented the dismantling of numerous authoritarian enclaves in the Senate, the Constitutional Council, the bureaucracy, and the armed forces, but also due to caution on the part of the political elite of the center-left. They felt that to even suggest any eventual repetition of the Allende experiment or attempt to judge those who had carried out human rights violations would endanger the precarious transition negotiated with the vigilant military, still headed by Pinochet, as well as upset the entrepreneurs who, having increased their wealth and power under the dictatorship, held the keys to the economy.

There were, in effect, two Allendes who died at La Moneda. One was the man who had given his life for democracy. The other was the revolutionary and anti-imperialist who believed there could be no solution to the ills besetting a country like Chile (and so many others in what was then called the third world), no way to be rid of poverty, inequality, and exploitation other than to radically transform the capitalist system. His funeral marked the apotheosis of Allende the democrat to the detriment of the revolutionary, who was sanitized, drained of all subversive, disorderly traits, and comfortably incorporated into the national pantheon. As for the hundreds of thousands who had been afforded the brief joy of watching this funeral from afar and offered the chimera that their memories mattered, they were now supposed to disband and leave governing to the experts. The streets were not for marching and making impossible demands.

For the next three decades, that compromise—yes to a monitored, restrained democracy, no to the risky adventure of a revolution—helped create political stability and faltering economic and social reforms that bettered the lives of the majority but kept in place one of the most unequal systems of income distribution in the world. During those years, Pinochet’s reputation sank to ever-lower depths, reaching its nadir when he was arrested in London in 1998 as a torturer, in a case that electrified public opinion worldwide and established the precedent that when former heads of state commit crimes against humanity, humanity has the right and duty to prosecute them beyond national borders.

Pinochet’s image was further diminished when in 2005 it was revealed that he and his family had illegally stowed more than $17 million in hidden accounts at Riggs Bank.

Meanwhile Allende became ever more legendary, ever more heroic, ever more honorable—and ever more distant.

Then, in October 2019, a revolt shook Chile. Student protests, savagely repressed by the police, turned into a full-scale popular insurrection. Everything was questioned: the penurious education, health, and housing systems; the pensions that, privatized under the dictatorship, enriched the companies and impoverished the elderly; the marginalization of women and indigenous communities; the persecution of gays and lesbians; a society of greed and consumption and rampant individualism.

And lo and behold, new life was breathed into Allende, the visionary prophet of a new order. His photo was held up on thousands of placards in the peaceful marches in which millions participated, his incendiary words adorned innumerable walls, and his name was invoked by masked militants who manned the barricades and battled the police with cobblestones and Molotov cocktails.

In order to channel the discontent of this frustrated and suddenly reawakened populace, a plebiscite was organized that asked voters if they wanted to replace Pinochet’s constitution. In October 2020, the measure passed with a walloping 78 percent of the vote and was followed in May 2021 by the election of delegates who would write a new constitution, with an overwhelming majority in favor of drastically altering how the country imagined itself.

As if this renewal of Chilean dreams of justice and equality was not enough, in December 2021 Gabriel Boric, a charismatic, tattooed, thirty-five-year-old former student leader, was elected president, defeating his rival, José Antonio Kast, an ultraright admirer of Pinochet, with almost 56 percent of the vote. It seemed that Boric’s vow that “if Chile was the cradle of neoliberalism, it will also be its grave” was about to come true.

Now Allende was not only in the streets and in the Constitutional Convention, but also once more entering La Moneda. On the day of Boric’s inauguration, the new president broke protocol: instead of walking directly into the presidential palace, he crossed the plaza to meditate for a minute in front of the statue of Allende that had been erected near the balcony from which he had waved good-bye to his pueblo thirteen years before Boric was born. The torch was being passed to a new generation, something that Boric emphasized at the end of his speech that evening:

As Salvador Allende predicted almost fifty years ago, we are again, fellow citizens, opening the grandes alamedas through which will pass the free man, the free men and women, to build a better society.

This vision of a different Chile was embodied in the constitution written in those months, which assigned rights to Nature, women, and indigenous communities, and made the state—not the market—responsible for the well-being of the people. I saw it as auspicious that the date of the referendum to ratify that new constitution was September 4, 2022. What better way of celebrating, fifty-two years after Allende’s victory and thirty-two after his burial, that the country he had anticipated, as both a democrat and a revolutionary, was becoming a reality? What better moment to say good-bye, not to Allende as we did when we marched past his receding figure, but to the dictatorship’s influence? It was not to be. The constitution that Allende would have revered and that embodied Boric’s dreams was rejected by almost 62 percent of voters.

Worse was to come. On May 7 of this year, the electorate chose the fifty delegates who will try again to write a new constitution. The right-wing parties obtained an overwhelming majority of thirty-four seats, with twenty-three of them belonging to the Partido Republicano led by Kast, who had been beaten emphatically by Boric and who has declared many times that he prefers to keep Pinochet’s constitution.

It is too soon to predict what this stunning change in the electorate’s fancies portends. Does it mean that we can expect Kast to become the country’s next president, one more Trump imitator in the southern hemisphere, another Bolsonaro? Does it signal a deep realignment of Chilean politics and priorities, with millions of Chileans who had not voted before now expressing their conservative opinions? Or were these electoral results merely a temporary blip, a protest against Boric’s inability to manage a series of cascading crises (crime, immigration, inflation, and violent conflicts between the state, large landowners, and indigenous communities)? Will he find a way to reformulate his program and regain the initiative?

The real question is where the true identity of Chile lies, a question that will again be debated as the fiftieth anniversary of the coup approaches. Did Pinochet’s neoliberal policies—and the terror he engendered—penetrate so deeply into the marrow of society that future projects of radical change are doomed to fail? Or are Allende’s grandes alamedas still beckoning all these years later? Will the horrors of the dictatorship be emphasized one more time and convince Chileans that they must reject anyone who does not strongly condemn the crimes of the Pinochet years?

Or will the mistakes of the Allende revolution be front and center, as a weary citizenry seeks a country that will never again be so polarized?

The wounds of Chile are deep, but regardless of how Chileans decide to deal with our trauma and conflicts, Allende’s legacy might have some bearing beyond the borders of his country. The need for radical change through nonviolence that this unique statesman posed—and did not achieve half a century ago—has again become the crucial issue of our era. With new variants of Pinochet troubling so many lands, Allende’s insistence throughout his life that for our dreams to bear fruit we need more democracy and never less—always, always more democracy—is more relevant than ever. He calls out to us that there can be no solution to the dilemmas plaguing the planet—war, inequality, mass migration, the twin threats of climate change and nuclear annihilation—without the active participation of vast majorities of fearless and enthusiastic men and women marching past the balconies of the future.

Fifty years after his death, Salvador Allende is still speaking to us.

_

Ariel Dorfman, a Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Literature at Duke, is the author of the play Death and the Maiden, the poetry collection Voices from the Other Side of Death, and, most recently, the novel The Suicide Museum. (September 2023)

Source:

https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2023/09/21/defending-allende-ariel-dorfman/