"What Is a Good Life ?" Ronald Dworkin

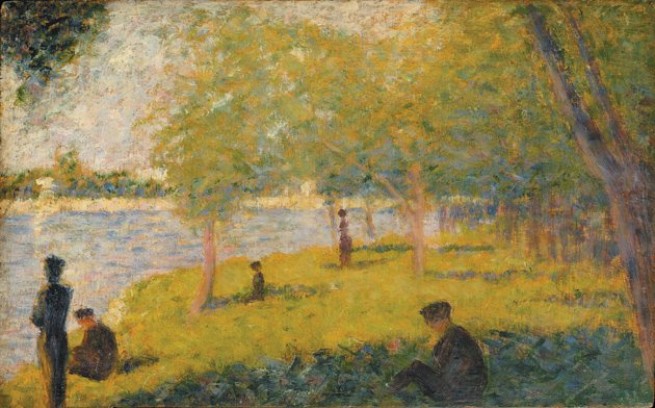

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York/Art Resource Georges Seurat: Study for ‘A Sunday on La Grande Jatte,’ 1884

Morality and Happiness

Plato and Aristotle treated morality as a genre of interpretation. They tried to show the true character of each of the main moral and political virtues (such as honor, civic responsibility, and justice), first by relating each to the others, and then to the broad ethical ideals their translators summarize as personal “happiness.” Here I use the terms “ethical” and “moral” in what might seem a special way. Moral standards prescribe how we ought to treat others; ethical standards, how we ought to live ourselves. The happiness that Plato and Aristotle evoked was to be achieved by living ethically; and this meant living according to independent moral principles.

We can—many people do—use either “ethical” or “moral” or both in a broader sense that erases this distinction, so that morality includes what I call ethics, and vice versa. But we would then have to recognize the distinction I draw in some other form in order to ask whether our ethical desire to lead good lives for ourselves provides a justifying moral reason for our concern with what we owe to others. Any of these different forms of expression would allow us to pursue the interesting idea that moral principles should be interpreted so that being moral makes us happy in the sense Plato and Aristotle meant.

In my book Justice for Hedgehogs—from which this essay is adapted—I try to pursue that interpretive project. We aim to find some ethical standard—some conception of what it is to live well—that will guide us in our interpretation of moral concepts. But there is an apparent obstacle. This strategy seems to suppose that we should understand our moral responsibilities in whatever way is best for us, but that goal seems contrary to the spirit of morality, because morality should not depend on any benefit that being moral might bring. We might try to meet this objection through a familiar philosophical distinction: we might distinguish between the content of moral principles, which must be categorical, and the justification of those principles, which might consistently appeal to the long-term interests of people bound by those principles.

We might argue, for example, that it is in everyone’s long-term interests to accept a principle that forbids lying even in circumstances when lying would be in the liar’s immediate interests. Everyone benefits when people accept a self-denial of that kind rather than each person lying when that is in his immediate interest. However, this maneuver seems unsatisfactory, because we do not believe that our reasons for being moral depend on even our long-term interests. We are, most of us, drawn to the more austere view that the justification and definition of moral principle should both be independent of our interests, even in the long term. Virtue should be its own reward; we need assume no other benefit in doing our duty.

But that austere view would set a severe limit to how far we could press an interpretive account of morality: it would permit the first stage I distinguished in Plato’s and Aristotle’s arguments, but not the second. We could seek integration of the ethical and moral within our distinctly moral convictions. We could list the concrete moral duties, responsibilities, and virtues we recognize and then try to bring these convictions into interpretive order—into a mutually reinforcing network of ideas defining our moral responsibilities. Perhaps we could find very general moral principles, like the utilitarian principle, that justify and are in turn justified by these concrete requirements and ideals. Or we could proceed in the other direction: setting out very general moral principles that we find appealing, and then seeing whether we can match these with the concrete convictions—and actions—we find we can approve. But we could not set the entire interpretive construction into any larger web of value; we could not justify or test our moral convictions by asking how well these serve other, different purposes or ambitions that people including ourselves might or should have.

That would be disappointing, because we need to find authenticity as well as integrity in our morality, and authenticity requires that we break out of distinctly moral considerations to ask what form of moral integrity fits best with the ethical decision about how we want to conceive our personality and our life. The austere view blocks that question. Of course it is unlikely that we will ever achieve a full integration of our moral, political, and ethical values that feels authentic and right. That is why living responsibly is a continuing project and never a completed task. But the wider the network of ideas we can explore, the further we can push that project.

The austere view that virtue should be its own reward is disappointing in another way. Philosophers ask why people should be moral. If we accept the austere view, then we can only answer: because morality requires this. That is not an obviously illegitimate answer. The web of justification is always finally, at its limits, circular, and it is not viciously circular to say that morality provides its own only justification, that we must be moral simply because that is what morality demands. But it is nevertheless sad to be forced to say this. Philosophers have pressed the question “why be moral?” because it seems odd to think that morality, which is often burdensome, has the force it does in our lives just because it isthere, like an arduous and unpleasant mountain we must constantly climb but that we might hope wasn’t there or would somehow crumble. We want to think that morality connects with human purposes and ambitions in some less negative way, that it is not all constraint, with no positive value.

I therefore propose a different understanding of the irresistible thought that morality is categorical. We cannot justify a moral principle just by showing that following that principle would promote someone’s or everyone’s desires in either the short or the long term. The fact of desire—even enlightened desire, even a universal desire supposedly embedded in human nature—cannot justify a moral duty. So understood, our sense that morality need not serve our interests is only another application of Hume’s principle that no amount of empirical discovery about the state of the world can establish conclusions about moral obligation. My understanding of a proposal for combining ethics and morality does not rule out tying them together in the way Plato and Aristotle did, and in the way our own project proposes, because that project takes ethics to be, not a matter of psychological fact about what people happen to or even inevitably want or take to be in their own interest, but itself a matter of ideal.

We need, then, a statement of what we should take our personal goals to be that fits with and justifies our sense of what obligations, duties, and responsibilities we have to others. We look for a conception of living well that can guide our interpretation of moral concepts. But we want, as part of the same project, a conception of morality that can guide our interpretation of living well.

True, people confronted with other people’s suffering do not normally ask whether helping those people will create a more ideal life for themselves. They may be moved by the suffering itself or by a sense of duty. Philosophers debate whether this makes a difference. Should people help a child because the child needs help or because it is their duty to help? In fact both motives might well be in play along with hosts of others that a sophisticated psychological analysis might reveal, and it might be difficult or impossible to say which dominates on any particular occasion.

Nothing important, I believe, turns on the answer: doing what you take to be your duty because it is your duty is hardly disreputable. Nor is it culpably self- regarding to worry about the impact of behaving badly on the character of one’s life; it is not narcissistic to think, as people often say, “I couldn’t live with myself if I did that.” In any case, however, these questions of psychology and character are not relevant to the question that I am posing here. Our question is the different one of whether, when we try to fix, criticize, and ground our own moral responsibilities, we can sensibly assume that our ideas about what morality requires and about the best human ambitions for ourselves should reinforce each other.

Hobbes and Hume can each be read as claiming not just a psychological but an ethical basis for familiar moral principles. Hobbes’s putative ethics—that self-interest and therefore survival are the greatest good—is unsatisfactory. At least for most of us, just achieving survival through a morality of self-interest is not a sufficient condition of living well. Hume’s sensibilities, translated into an ethics, are much more agreeable, but experience teaches us that even people who are sensitive to the needs of others cannot resolve moral, or ethical, issues—as Hume’s theory might suggest—simply by asking themselves what they are naturally inclined to feel or do. Nor does it help much to expand Hume’s ethics into a general utilitarian principle. The idea that each of us should treat his own interests as no more important than those of anyone else has seemed an attractive basis for morality to many philosophers. But as I shall shortly argue, it can hardly serve as a strategy for living well oneself.

Religion can provide a justifying ethics for people who are religious in the right way; we have ample illustration of this in the familiar moralizing interpretations of sacred texts. Such people understand living well to mean respecting or pleasing a god, and they can interpret their moral responsibilities by asking which view of those responsibilities would best respect or most please that god. But that structure of thought could be helpful, as a guide to integrating ethics and morality, only for people who treat a sacred text as an explicit and detailed moral rule book. People who think only that their god has commanded love for and charity to others, as I believe many religious people do, cannot find, just in that command, any specific answers to what morality requires. In any case, I shall not rely on the idea of any divine book of detailed moral instruction here.

The Good Life and Living Well

If we reject Hobbesean and Humean views of ethics and are not tempted by religious ones, yet still propose to unite morality and ethics, we must find some other account of what living well means. As I said, it cannot mean simply having whatever one in fact wants: having a good life is a matter of our interests when they are viewed critically—the interests we should have. It is therefore a matter of judgment and controversy to determine what a good life is. But is it plausible to suppose that being moral is the best way to make one’s own life a good one? It is wildly implausible if we hold to popular conceptions of what morality requires and what makes a life good. Morality may require someone to pass up a job in cigarette advertising that would rescue him from poverty. In most people’s view he would lead a better life if he took the job and prospered.

SUITE :

http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2011/feb/10/what-good-life/